Yellow fever is an acute viral haemorrhagic disease transmitted by infected mosquitoes. The “yellow” in the name refers to the jaundice that affects some patients.

Signs and symptoms

Once contracted, the yellow fever virus incubates in the body for 3 to 6 days. Many people do not experience symptoms, but when these do occur, the most common are fever, muscle pain with prominent backache, headache, loss of appetite, and nausea or vomiting. In most cases, symptoms disappear after 3 to 4 days. A small percentage of patients, however, enter a second, more toxic phase within 24 hours of recovering from initial symptoms. High fever returns and several body systems are affected, usually the liver and the kidneys. In this phase people are likely to develop jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes, hence the name ‘yellow fever’), dark urine and abdominal pain with vomiting. Bleeding can occur from the mouth, nose, eyes or stomach. Half of the patients who enter the toxic phase die within 7 – 10 days.

Diagnosis

Yellow fever is difficult to diagnose, especially during the early stages. A more severe case can be confused with severe malaria, leptospirosis, viral hepatitis (especially fulminant forms), other haemorrhagic fevers, infection with other flaviviruses (such as dengue haemorrhagic fever), and poisoning.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing in blood and urine can sometimes detect the virus in early stages of the disease. In later stages, testing to identify antibodies is needed (ELISA and PRNT).

Populations at risk

Forty seven countries in Africa (34) and Central and South America (13) are either endemic for, or have regions that are endemic for, yellow fever. A modelling study based on African data sources estimated the burden of yellow fever during 2013 was 84 000–170 000 severe cases and 29 000–60 000 deaths.

Occasionally travellers who visit yellow fever endemic countries may bring the disease to countries free from yellow fever. In order to prevent such importation of the disease, many countries require proof of vaccination against yellow fever before they will issue a visa, particularly if travellers come from, or have visited yellow fever endemic areas.

In past centuries (17th to 19th), yellow fever was transported to North America and Europe, causing large outbreaks that disrupted economies, development and in some cases decimated populations.

Transmission

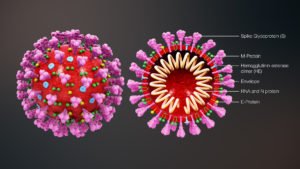

The yellow fever virus is an arbovirus of the flavivirus genus and is transmitted by mosquitoes, belonging to the Aedes and Haemogogus species. The different mosquito species live in different habitats – some breed around houses (domestic), others in the jungle (wild), and some in both habitats (semi-domestic). There are 3 types of transmission cycles:

- Sylvatic (or jungle) yellow fever: In tropical rainforests, monkeys, which are the primary reservoir of yellow fever, are bitten by wild mosquitoes of the Aedes and Haemogogus species, which pass the virus on to other monkeys. Occasionally humans working or travelling in the forest are bitten by infected mosquitoes and develop yellow fever.

- Intermediate yellow fever: In this type of transmission, semi-domestic mosquitoes (those that breed both in the wild and around households) infect both monkeys and people. Increased contact between people and infected mosquitoes leads to increased transmission and many separate villages in an area can develop outbreaks at the same time. This is the most common type of outbreak in Africa.

- Urban yellow fever: Large epidemics occur when infected people introduce the virus into heavily populated areas with high density of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and where most people have little or no immunity, due to lack of vaccination or prior exposure to yellow fever. In these conditions, infected mosquitoes transmit the virus from person to person.

Treatment

Good and early supportive treatment in hospitals improves survival rates. There is currently no specific anti-viral drug for yellow fever but specific care to treat dehydration, liver and kidney failure, and fever improves outcomes. Associated bacterial infections can be treated with antibiotics.

Prevention

1. Vaccination

Vaccination is the most important means of preventing yellow fever.

The yellow fever vaccine is safe, affordable and a single dose provides life-long protection against yellow fever disease. A booster dose of yellow fever vaccine is not needed.

Several vaccination strategies are used to prevent yellow fever disease and transmission: routine infant immunization; mass vaccination campaigns designed to increase coverage in countries at risk; and vaccination of travellers going to yellow fever endemic areas.

In high-risk areas where vaccination coverage is low, prompt recognition and control of outbreaks using mass immunization is critical. It is important to vaccinate most (80% or more) of the population at risk to prevent transmission in a region with a yellow fever outbreak.

There have been rare reports of serious side-effects from the yellow fever vaccine. The rates for these severe ‘adverse events following immunization’ (AEFI), when the vaccine provokes an attack on the liver, the kidneys or on the nervous system are between 0 and 0.21 cases per 10 000 doses in regions where yellow fever is endemic, and from 0.09 to 0.4 cases per 10 000 doses in populations not exposed to the virus (1).

The risk of AEFI is higher for people over 60 years of age and anyone with severe immunodeficiency due to symptomatic HIV/AIDS or other causes, or who have a thymus disorder. People over 60 years of age should be given the vaccine after a careful risk-benefit assessment.

People who are usually excluded from vaccination include:

- infants aged less than 9 months;

- pregnant women – except during a yellow fever outbreak when the risk of infection is high;

- people with severe allergies to egg protein; and

- people with severe immunodeficiency due to symptomatic HIV/AIDS or other causes, or who have a thymus disorder.

In accordance with the International Health Regulations (IHR), countries have the right to require travelers to provide a certificate of yellow fever vaccination. If there are medical grounds for not getting vaccinated, this must be certified by the appropriate authorities. The IHR is a legally binding framework to stop the spread of infectious diseases and other health threats. Requiring the certificate of vaccination from travelers is at the discretion of each State Party, and it is not currently required by all countries.

![]()